-

Chapter 1 – The Newbould Family & Meadow Bank Avenue

Chapter 1:

The Newbould Family and Meadow Bank Avenue

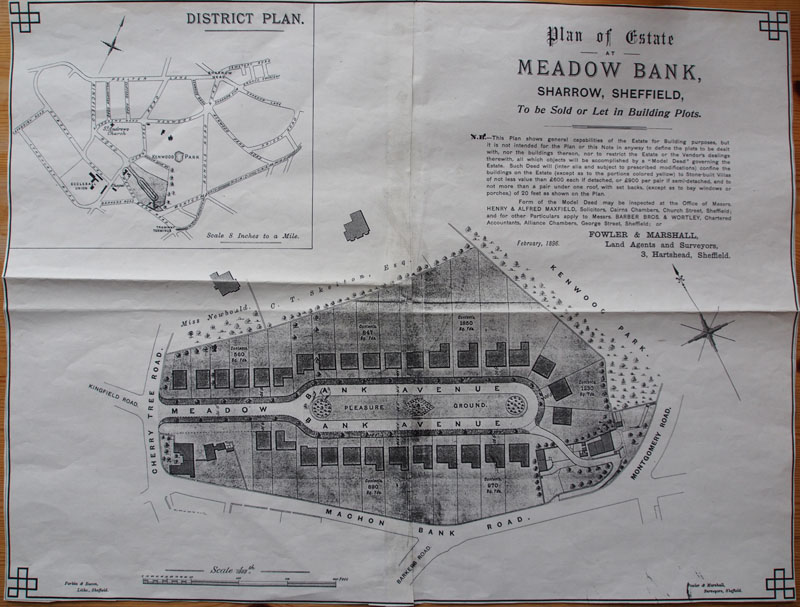

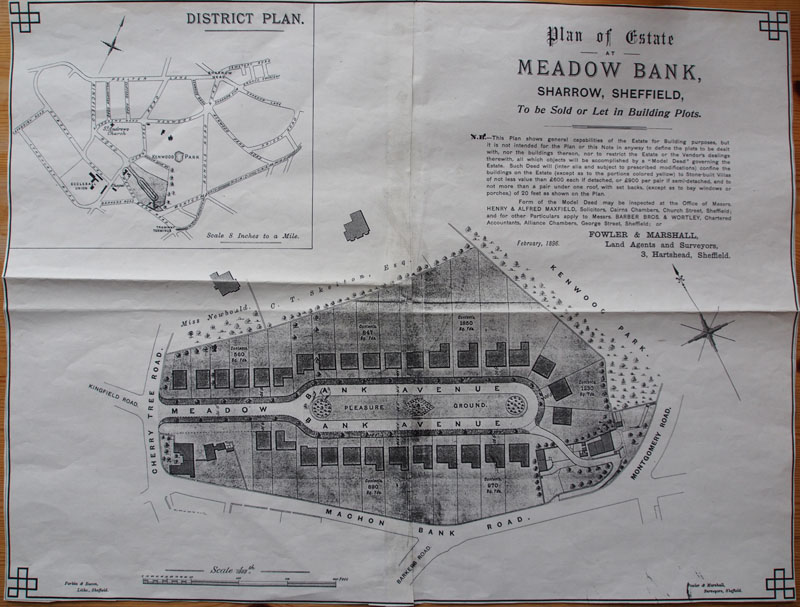

In February 1896, Sheffield surveyors Fowler and Marshall produced a beautiful plan showing the development potential of the Meadow Bank Estate in Sharrow. It was to be built on land owned by Miss Elizabeth Newbould and entry to the estate would be from Cherry Tree Road. The most notable feature of the planned development would be the large, central ‘pleasure ground’ (complete with formal flower beds) designated for the sole use of residents.

The road itself was to be surrounded by a wide, tree-lined pavement and all building development would be governed by a ‘Model Deed’. This meant that all those purchasing land were bound by strict stipulations relating to the type of houses, their value and usage. Miss Newbould retained ownership of the pleasure ground, road and footpaths and agreed for her part to maintain them for the benefit of all residents. Existing and future owners of the plots covenanted to maintain their house frontages (through annual payments) and also to keep their homes as private houses. This is how Meadow Bank Avenue came into existence, but there is far more to the history of the Meadow Bank Avenue estate and its community.

February 1896 plan

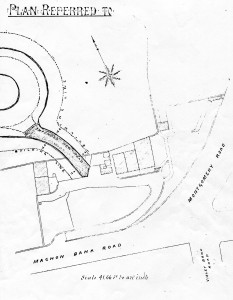

What might come as a surprise is that another plan for Meadow Bank Avenue had been proposed earlier in 1896 and this was far less ambitious. It took the form of a modest crescent, looping from the top of Machon Bank to the lower end of Cherry Tree Road.

First suggested plan 1896

We don’t know why Elizabeth chose the more ambitious plan; it was not a common model of development in Sheffield. Certainly she stood to gain more financially if the second plan could be brought to fruition, because it made much better use of the whole plot of land and would accommodate more housing. There might perhaps have been other factors influencing her. By the 1880’s she was living in Leamington Spa, in Clarendon Avenue and then Dale Street. Both of these addresses are very close to Beauchamp and Clarendon Squares – elegant, private spaces with central greens. It might be a coincidence but it could be that Elizabeth wanted to create something special in Nether Edge, having enjoyed the squares in Leamington Spa.

1905 OS Map of Leamington Spa

A great debt is owed to Elizabeth Newbould for her visionary plan, particularly as much of the development that was taking place in Sheffield and other industrial cities in the late nineteenth century was rapid, unplanned and often unattractive. As Sheffield spread into the valleys and hills that surrounded the city centre, jerry-built houses were constructed at high density. The developers were often criticised in local newspapers and public lectures but it was difficult to stop them once land had been purchased.

One effective and practical solution was for individuals or groups to set up Land Societies. It’s important to understand how these functioned because they had a major impact on Nether Edge. These early building societies bought up plots of land in the threatened suburbs of the south and south west of the city and imposed building constraints on any future development. The constraints related to a range of things, including, for example, building materials, height, windows and restrictions on usage. The Montgomery Land Society, founded in 1861, was a good example. It was set up to purchase a large piece of land through its trustees. This was then to be divided amongst the Society’s members and sold as small plots, which would be paid for in instalments. In this way people of moderate means could become freehold landowners. George Wostenholm was also active in controlling developments within land that he controlled in Nether Edge from the 1850s, restricting any type of commercial or industrial activity ‘deemed offensive to the neighbourhood’. He also banned public houses, bowling greens, tea gardens and other places of amusement from the Kenwood estate.

Elizabeth Newbould’s family was very involved in the land society movement. She had grown up in a house named ‘Sharrow Bank’, which occupied the south corner of Cherry Tree Road and Psalter Lane, across the road from where St Andrew’s Church now stands. The house fell into disrepair in the late twentieth century and was demolished some years ago. It was replaced by a small housing development, but ‘Sharrow Bank’ had been a very handsome house when it was bought by the Newboulds in 1820. It occupied a large plot of land stretching back to Clifford Road and Henry Newbould and his wife Mary (nee Williamson) had plenty of space in which to bring up their four children. Elizabeth’s older brother, William, married and had six children. Another brother, Henry, died in his thirties. Elizabeth and her twin brother, John (born in 1823), remained single all their lives. John became a lawyer with a practice in Paradise Square and was Auditor of the Sheffield Law Society until he died in 1880. After John’s death, Elizabeth left ‘Sharrow Bank’ and Sheffield, moving to Leamington Spa to live with her cousin Samuel. Her remaining older brother William died in 1886.

The Newbould’s were prosperous business people. Henry, Elizabeth’s father, was initially in the family firm of Sanderson and Newbould, manufacturers of machine tools. He also had an interest in acquiring property. This funded the family’s gracious lifestyle at ‘Sharrow Bank’. The grounds contained a carriage house and three large greenhouses – space for their collection of camellias and azaleas. There was a good library and fine wine cellars, expensive furniture and beautiful silver and glassware. We know all this because, when the house contents were sold, the sale took seven days and the sale catalogue detailed hundreds of items for auction. The Newboulds had influential neighbours; George Wostenholm had begun to build ‘Kenwood Park’ in 1844, and he went on to develop the tree-lined avenues of Kenwood that we know and love today. Just along the lane from ‘Sharrow Bank’, Sir John Brown’s home ‘Shirle Hill’ was grand enough to be visited by the Prime Minister Lord Palmerston in 1868.

Sharrow Bank – home of Elizabeth Newbould

As a member of the Montgomery Land Society, Elizabeth’s brother John Newbould bought plots of land in the Nether Edge area. Elizabeth could see the results of covenants and the constraints that could be brought to bear on developers; the good stone houses with gardens and gated roads. There were, by that time, other covenanted gated communities in places like Endcliffe, Ranmoor and Collegiate Crescent, of which the family would have been aware. Elizabeth inherited a great deal of property and land from her father (on his death in 1871) and from her brother John in 1880. There was a Chancery Court case to agree a settlement to the family of her deceased brother, William, and this matter was finally concluded in 1895, when Elizabeth was assigned all property in the Township of Sheffield, Brightside, Upper Hallam, Attercliffe- cum-Darnall, Ecclesall Bierlow, the Parish of Heeley, Township of Stannington and the Parish of Ecclesfield. Locally it meant that she owned land from Psalter Lane to Lyndhurst Road, Edgedale Road, Edge Bank and Cherry Tree Farm and the fields beyond it. It was this last parcel of land which would become Meadow Bank Avenue in 1896. Elizabeth covenanted all of her land; an action that was in keeping with the informed and educated spirit of her neighbours. It meant that there were restrictions on both the builders and the purchasers of houses on her land.

It is to Elizabeth that we owe our special environment and her vision is an important strand in the history of Meadow Bank Avenue, but there are other factors to consider too. Much of Sheffield was still very rural until the middle of the nineteenth century. Areas like Nether Edge were characterised by small farmsteads, smithies and workshops, where traditional small-scale industry and farming operated side by side. This sketch shows a farm on Machon Bank Road in 1878. We can’t be absolutely sure but this may well be Cherry Tree Farm which stood at the top of Machon Bank before the building of the Avenue.

Sketch of Machon Bank Farm 1878

Sheffield was essentially a working class city; it wasn’t a grand commercial centre with an impressive civic centre. Large-scale production of steel and metal goods in large factories was a relatively late development and the city’s poor transport networks meant it was somewhat cut off from other centres.

Our city’s tradition was one of smaller scale production and specialised, highly-skilled craftsmanship. Then the boom time came in the mid nineteenth century and much larger works were built along the river valleys. The population grew from 65,275 in 1821 to 110,891 in 1841, then more than doubled again by 1877 to reach 282,130. This explains why there was so much pressure to build cheap housing for the working classes.

The people who were fighting to save the suburbs were mostly ‘self-made’ men who amassed fortunes and wanted to enjoy the fruits of their labour away from the smoke of their enterprises. The list of individuals serving on the Municipal Council between 1843 and 1893 is a list of people knowledgeable in all aspects of metal work, and trades and professions to service that dominating interest. It is worth noting that few people were listed as ‘Gentlemen’. The land societies, and people like Elizabeth Newbould, were building for these successful Sheffield folk – not for the very rich, but for the ‘rich enough’.

You might want to look at the maps section of the website to see how the city was changing during this time. In 1807 Fairbanks surveyed Sheffield and a simplified, modern interpretation of the survey illustrates how sparsely populated Nether Edge was at that time. Only a few farms, smithies and crofts occupied the lower end of Cherry Tree Road. Similarly, the 1840 Ordnance Survey map shows a Nether Edge still characterised by small enterprises, with just a few larger houses. By 1892/3 this was beginning to change. The 1893 OS map features a new workhouse, chapel, public house and several new or planned areas of housing.

Cherry Tree and Machon Bank before Meadow Bank Avenue

Before we look at the building of Meadow Bank Avenue we need to understand a little more about Cherry Tree and its immediate surroundings at that time. Cattle grazed in the nearby fields around Cherry Tree Hill when Elizabeth was growing up at ‘Sharrow Bank’ and the old Cherry Tree Lane was little more than a narrow farm track. If she walked along it she would have passed the fields belonging to Mary Naw on her right and the Ludlam’s smithy on her left. Beyond that lay Cherry Tree Farm, a very peaceful farmstead and, facing it on the other side of the lane, Wisteria Cottage, built in 1765 by Robert Bagshawe, a scythesmith. Scythemaking was very common in the neighbourhood with several smithies operating along Machon Bank.

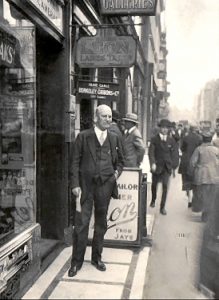

Cherry Tree Farm 1905

Cherry Tree Farm had been built in 1673 by Robert Savage, a cutler. Beside it was Thomas Ludlam’s house, which dated from 1658. The fields belonging to Cherry Tree Farm were the Mow Meadow Bank, The Great Croft, The Little Croft, North Lower Close and South Lower Close. There was also a small plot on the other side of Cherry Tree Lane which was part of Dobbin Croft. The farm was passed down through the descendants of Robert Savage until it was bought by Samuel Greaves of Greystones in 1818 – and his descendants sold it to John Newbould, who bequeathed it to his twin sister Elizabeth. It was these fields which were developed into Meadow Bank Avenue.

In 1896, when the Fowler and Marshall plan for the Meadow Bank Avenue estate was drawn, Cherry Tree Farm still stood on the corner of Machon Bank and Cherry Tree Road. The farmstead wasn’t demolished for another decade, after part of the Avenue had already been built. We have some interesting evidence of the farm’s structure and layout. Its last tenants were Mr Christopher Ibbotson and his family. The gateway into the farmyard was on Cherry Tree Road and the entrance to the farmhouse was in Machon Bank, opposite the Union Hotel. The house was built in 1673 and demolished in 1907. At some time in its history it had been used as a tithe barn in connection with a priory on Priory Road. A descendant of the last tenant reported that the internal rooms were partitioned with oak and the outside walls were three feet thick.

The lovely picture of the farm, taken in 1905, shows Mr Ibbotson in front of a well-kept house with a productive vegetable garden. The gable of the Union Hotel can just be seen on the left.

Just before it was pulled down Miss Edith Leader visited the old farm to record historical details for her Father. This is the text of her letter;

279, Glossop Road,

Sheffield

July 30th 1907.

My Dearest Father,

I have been spending the morning, between thunder showers, in sketching the old house at Machon Bank and though the weather interfered a good deal and I am afraid the perspective is not absolutely correct, it gives a better idea of it than the picture in the Telegraph. It stands at the corner of Machon Bank Road and Cherry Tree Road, as you will see with its back to Cherry tree Road and facing east – down the hill at any rate. From the rough plan you will see the relationship of stables and living house. I could not get in and it looked very dirty, but both rooms were panelled, one up to the ceiling, the other half way: the woodwork is painted so I could not see if it was anything but deal. They are very small rooms, and I don’t know what is behind – kitchens I suppose.

In the gable bonding to the barn there are two windows and a door and it looks as if lately it had been a separate cottage. The letters and figures TL 1658 in the barn gable are very large, and are simply sunk in the masonry- and on the other corresponding gable facing Machon Bank Road are the letters G I. I looked to see if it could be the upstroke of an L but there was no sign of the foot. They are sunk too. The stable is a very large place with giant beams across, it is not ceiled but goes straight up to the roof. There is a separate building like another barn, which has a dripstone built into a brick gable, the window is blocked up. This does not appear in the photograph but I have put it in my picture.

It was very tiresome of it to rain, but a very nice workman came and found me sheltering under a big door into the stable and took me into the barn. If there is anything more you would like to know I can easily go again. I am sorry I did not ask the man if he could let me into the house. He says it was inhabited until about a year ago.

Please thank Mother for her long letter, just received. I will write tomorrow in answer.

It has cleared up into a lovely sunny afternoon.

With much love,

I am ever,

Your loving daughter,

Edith E. Leader

We also know that it was demolished by the firm of Abbott and Bannister who subsequently built houses at the top of Machon Bank as well as on Meadow Bank Avenue. They discovered a cast iron fireplace support bearing the date 1669 during the demolition and this was sent to Weston Park Museum. In September 1908 they also clarified the initials on the building. The date stone on the farm house was R.S. 1673; the lettering on the barn gable fronting Meadow Bank Avenue was T.L. 1658 and the gable end fronting Machon Bank read G.L. No date was found behind the lean-to addition to the farm.

We have another photograph that was taken during the course of demolition in 1907, possibly by Mr Abbott.

This was provided by Mrs Vera Toothill, the aunt of Sheila Marshall, who lived with her husband Philip at number 29 Meadow Bank Avenue from 1959-1982. Vera was born in 1897, the daughter of Mr Abbott, the local builder mentioned above. Every night the firm’s horses would be led up through Nether Edge to graze on the fields of Cherry Tree Farm. Vera would ride on the horses as they were led by the workmen, who would then take her back to her parents’ house on Machon Bank. Vera died in her 99th year in 1996. When she sent the photograph to Sheila and Philip in 1982 it was accompanied by this little note:

Dore, 30/10/1982

My Dears,

Just a short note to send the photo. I think I am about the only person in Sheffield to remember Cherry Tree Farm. It is all so long ago, eighty years or so, and the country lanes and quiet life seems never to have been’

Auntie Vera

-

Chapter 2 – Building the Avenue

Chapter 2:

BUILDING THE AVENUE

This section of the website examines the relatively slow process of constructing the Meadow Bank Avenue Estate. It concentrates on the physical elements of the Avenue rather than its early residents; they will be the subject of another chapter. The process of selling the plots and building the 50 houses which now make up Meadow Bank Avenue has been divided into three phases; 1896–1908, 1909–1920 and 1921–1936. However, before we examine the first phase of building the Estate it’s important to understand the significance of Elizabeth Newbould’s final land acquisition, Edge Bank. We’ll also acknowledge other local developments which had an impact on Nether Edge, the Avenue and its residents.

I. Edge Bank and its links to the Meadow Bank Avenue Estate

In 1886, when Elizabeth inherited the land on which Meadow Bank Avenue would later be built, it did not provide any access to Machon Bank, but in 1894 she acted to change this. She purchased more land, acquiring the whole of Edge Bank at a cost of £1,800 from Henry Elvidge, who had inherited it just five years earlier from his father Samuel Elvidge, a farmer by occupation. For much of the nineteenth century, however, Edge Bank had been owned and developed by the Boot family. The Boots made a significant contribution to Nether Edge and to our own community, not least because they built and established the Union Hotel, a facility still greatly enjoyed by many Avenue residents.

The Union Hotel and hansom cab rank c.1900

The Boot Family of Edge Bank

Edge Bank was owned by the Boot family until 1867 and in 1837 Charles and Joseph Boot, stonemasons and builders by trade, had built the stone cottages, numbers 1,2,3,4 and 5, which still stand on Edge Bank (pictured below). Charles, his wife Sarah and 8 children lived in one of the cottages for the rest of his life; he died in 1867 at the age of 62 having retired some years earlier. His wife Sarah continued to live in the Edge Bank cottage, although she changed her name to Boote, perhaps an early sign of gentrification in Nether Edge.

In 1849 the Boots had built the Union Hotel and the two stone houses either side of it. The Union would have had a steady trade from the workmen building the new Ecclesall and Bierlow workhouse (now the gated Nether Edge estate on Union Road), which was started in 1841. Union was another name for workhouse at that time, hence the naming of the road and the pub. Joseph became the first landlord of the new pub, a job he did for thirty years whilst continuing to work as a stonemason and quarry owner. He moved from Edge Bank to live at the Union with his wife and 7 children. By late 1871 he had left the pub to live at 11 Union Road, where he died in 1880. Four years earlier (1876) he too had opted for the more refined surname of Boote.

It was the cousins of the Edge Bank Boots who were to start the more famous Sheffield firm of Henry Boot. In 1886 Henry started the building firm at the age of 35. They built large houses, cinemas and pubs in the city and some of the ceremonial arches that were erected for Queen Victoria’s visit to Sheffield in 1897. The Applied Sciences Building at the University of Sheffield was another major project and during the First World War the company won contracts to construct army camps.

It is recorded in the West Riding Registry that Elizabeth purchased 2940 square yards of land on Edge Bank and the five messes or dwelling houses already built on it. At the time these were occupied by Mrs Needham, W.S.Playle, William Knight, John Baggalley and Mrs Stables.

Miss Newbould’s Purchase of Edge Bank 1894

This important acquisition would give her frontage onto Machon Bank Road and Montgomery Road and the following year, in 1895, Elizabeth applied to the Corporation for permission to build a new roadway connecting the lower end of Meadow Bank Avenue to the old Edge Bank track down to Machon Bank Road. Edge Bank was already gated at the bottom of the slope before the extension was built at the top to join it to the new Avenue.

The Plan for the New Road linking the Avenue to Edge Bank 1895

On the Fowler and Marshall 1896 Plan (see Chapter 1 of The Avenue Story) illustrating the capabilities of the Meadow Bank Avenue Estate, the new roadway was clearly shown in place. The extension is still visible today as the cobbled section of Edge Bank. It gave Avenue residents better access to the shops and services of Nether Edge and, perhaps more importantly, provided a short-cut to the trams. This would become a strongly-emphasised benefit when land and houses on Meadow Bank Avenue came up for sale.

Nether Edge Trams and Transport to Work

Initially transport into the city centre from the new suburb of Nether Edge would have been by hansom cab or horse tramway. Horse trams were privately owned services, developed after the passing of the Tramways Act of 1870. They gave customers a more comfortable ride than the older horse bus service but they were relatively expensive, especially for lower paid workers. As the city grew it became clear that a more efficient, cheaper transport system was needed. When the lease ran out for the old Sheffield Tramways Company in 1896 the Corporation stepped in to develop a municipal service.

From September 1896 a new electric tram service, operated by Sheffield Corporation, ran between the city centre and Nether Edge terminus; it was the first electric tram line to be opened in the city, marking the beginning of an important new transport network. A depot and tram shed were built on the site of what is now Sainsbury’s supermarket.

The new electric trams were quicker, smoother and coped better with the hills and bad weather. They were also very cheap – the fare was just one old penny (equivalent to 0.42p) for two and a half miles. The Nether Edge tramline lasted until 1934, when it was closed because of the narrowness of the roads; by that time cars and trams were competing for space.Nether Edge Tram Terminus c. 1900

II. The First Phase of Building Meadow Bank Avenue, 1896 -1909

House building began in 1896 very soon after the first plots of land had been sold. We have good sources of information on early land sales and house construction at the end of the nineteenth century but there is one very significant gap in our knowledge of the building of Meadow Bank Avenue; we don’t know who constructed its infrastructure. Fowler and Marshall were Elizabeth’s surveyors, so it is probable that they would have been responsible for determining the size and shape of the Pleasure Ground, the width of the pavements and roadway and other aspects, such as the positioning of the sewers and the prescribed building line. All of these are shown on the plan contained within the Deed of Mutual Covenants (see Chapter 1), but who built the beautiful walls, steps and entrances around the green? The quality of stonemasonry was high and all of these features were clearly in place at an early stage. We can see them on this postcard photograph of the Avenue dated 1906:

The Avenue in 1906 ; houses 49 and 51 at the end of the Pleasure Ground and numbers 30 – 42 to the right (south side)

Although the flower beds illustrated on the original 1896 sale plan had not materialised, the green was flourishing and good enough for a game of tennis. By this time the lime trees were also well-established, their trunks protected by metal supports.

It might be that the walls around the green were built by Bannister and Abbott. They were very local and had strong connections with the land to be developed (see Chapter 1; section on Cherry Tree Farm). They were also early developers of plots of land on both the Avenue and Machon Bank Road – but we have no definite proof that they built the walls. Other local builders such as the Boot family or Henry and Robert Brumby might have undertaken the work. As explained earlier in this chapter, the Boot family were builders and stonemasons and they would have had easy access to the materials required for building the walls because they owned a quarry at Brincliffe Edge. We also know that between 1897 and 1900 the Brumby’s held contracts with Elizabeth Newbould; they were busy building Ladysmith Avenue and Edgebrook Road on land owned by her.

Whatever the origin of the Avenue infrastructure we know for certain that, on the 31st August 1896, John Wortley and Sleigh Bush bought the first plot of land at the far end of the Pleasure Ground. Joshua Wortley and Sons were Elizabeth’s accountants and Bush was an auctioneer. Another accountant, Henry Belk, is also listed as having purchased a plot of 702 square yards at the other end of the new development. This was recorded two days later on 2nd September 1896. Henry was a partner in the local firm of Oakes, Belk and Skinner, Stockbrokers and Accountants.

Wortley, Bush and Belk each signed the first Deed of Mutual Covenants. Compliance with the terms of this important document would be a condition imposed on all future purchasers and residents of the Avenue. The Deed had been carefully drafted by Elizabeth’s solicitors, Henry and Alfred Maxwell and it bore the same date as the first purchase, 31st August 1896. A copy of the original Deed of Mutual Covenants can be accessed here. It is not an easy read, especially in its original handwritten format, so we are very grateful to Nick Waite for his clear explanation of its key points.

When we started to accumulate material for the Meadow Bank Avenue History project in 1996, Nick (a Sheffield solicitor and former resident of number 33) very kindly reviewed all of the legal documents relating to the development of the Avenue. Extracts from his overview of the Avenue’s Legal Framework are included in the rest of this chapter, beginning with the Deed, which still remains in place;The Deed of Mutual Covenants

Objectives of the Deed:

1. To control the development of the individual plots.

2. To provide a mechanism for the maintenance of the pleasure ground, road and footpaths.

3. To ensure that the necessary finance was available.

These objectives were achieved by the ‘covenants’ given by each party. (A covenant is a signed and sealed, legally-binding promise; anyone defaulting on a covenant can, if necessary, be sued.)The Covenants

Miss Newbould, and her ‘successors in title’ (those who purchased the Estate from her) covenanted to lay out and maintain the roads, footpaths, sewers and pleasure ground until they were adopted by the local authority. She also covenanted to permit the Purchasers to use the same in connection with their own use and occupation of the individual plots, provided the Purchasers played their part in the arrangement.

The Purchasers’ side of the bargain was as follows; firstly to pay their contributions to Miss Newbould to cover her expenditure on the maintenance, and secondly to pay any contribution required either by her or the local authority, if and when the Estate was adopted. The method of apportioning the payments was to be levied in proportion to the frontage length of the land of each Purchaser.

Stipulations:

Having set out the basic structure for maintenance and payment, the Deed then provided mutual covenants and the actual and future Purchasers, by which each promised to observe and uphold Stipulations set out in a schedule to the Deed. The Stipulations are rules which govern the size, value, appearance, position and fencing of the houses to be built.- Size: No buildings to be built other than detached or semi-detached houses, not exceeding 2 storeys in height viewed from the road, together with stabling, conservatories, greenhouses, offices and outbuildings to be used with the house.

- Value: Houses were to be worth over £600 for a detached and £900 for each pair of semi-detached.

- Appearance: All buildings had to be cased externally with rock-faced stone, except the upper part which could be half-timbered, pebble-dashed or hung with tiles, subject to approval.

- Position: All buildings were to be set back to the building line shown on the plan, except for porches and bay windows and the land between the building line and the road was only to be used as an ornamental pleasure ground. No window, light, door or other opening was to be made in any building, wall or fence erected on the boundary with another property.

- No building was to be used as a boarding or other type of school or other than a private dwelling, or uses ancillary to a dwelling house. No trade, manufacture, business or profession of any kind should be set up; the only exceptions were the professions of ‘Physician or Surgeon’ and more unusually, but only with Miss Newbould’s written consent ‘any business of an agricultural or gardening nature’

Wortley and Bush’s plot was the first sale. They paid £792 and the plot was a sizeable 3380 square yards. The first houses on Meadow Bank Avenue, numbers 49 and 51, were completed on it by September 1897. The two handsome semi-detached residences stood proudly at the end of the Pleasure Ground, but Wortley and Bush were in no hurry to add to them. The rest of their plot would remain undeveloped for almost forty years, until numbers 45, 47 and 47a were built on it.

Between September 1896 and 31st May 1900 other plots were sold to Ada Lydia Havenhand, Elizabeth Broomhead, and George Smith. It is perhaps surprising that some of the named purchasers were women but it was common then for business owners to put land and houses in the names of their wives or sisters. This safeguarded the property because the Bankruptcy Laws at that time meant that they could lose their homes if the business ran into financial difficulties. The order of building during this first phase of Avenue development was as follows:

1897: The Broomhead plot, comprising 797 square yards, was situated near the top of the Avenue on the left hand (north) side. In 1897, 3 Meadow Bank Avenue was built here.

1897-98: Numbers 22 and 24 were built for Miss Havenhand. The plot, bought in March 1897, was 904 square yards and the two homes were occupied by the Havenhands at number 24 and the Westons at number 22.

1899-1900: George Smith bought a plot of 716 square yards in April 1899, on which one detached house was built; this was number 34.

1900: Henry Belk’s land at the entrance to the Avenue (adjoining Miss Broomhead’s), plus an additional strip of 161 square yards, purchased by builders James and Fred Lee in April 1900, became the site of two semi-detached houses with frontages on Cherry Tree Road . Numbers 75 and 77 were completed by 1901.

1900-1902: Ten semi-detached Victorian villas were built on the south side of the Avenue; numbers 26 to 42. The builders were a Mr Fletcher of Chesterfield (26-32) and Mr Finch of Hull (36-42). The quality of Mr Fletcher’s Meadow Bank Avenue villas may have been an issue. Local records show that building inspectors made 64 visits to inspect the houses and drains of numbers 26-32 before they were finally approved.

1900 – 1902: Numbers 18 and 20 were also started by Fletcher in 1900. He couldn’t however finish the job; construction was taken over by the mortgagees and the houses had to be completed by Hancock and Son.

These tall houses with their decorated pointed gables and stone mullioned bay windows were a popular style in Sheffield’s new suburbs at the end of the nineteenth century. The photograph below was taken in 1907 by Wallace Evans Heaton, resident of number 36. You can read more about Wallace Heaton in the Biographies section of the website.34-42 Meadow Bank Avenue in 1907

If you look back at the February 1896 Fowler and Marshall Plan for Meadow Bank Avenue (see Chapter 1) you’ll notice that it envisaged a development of detached houses, but we can see from this first phase of development that land purchasers and builders were actually building more semi-detached homes. This might have been a way of maximising the return on their investment, or perhaps it reflected the economic status of their potential purchasers, the ‘rich enough’ small business owners and professionals who were setting up home in the new suburb of Nether Edge. It wasn’t uncommon for one purchaser to buy both of the semis and rent out one or both of the houses. We know that this happened on the Avenue, for example with numbers 40 and 42. ‘Buy to let’ is not a new trend; it was thriving in the late 19th century.

The Redevelopment of the Cherry Tree Farm site 1907-1909

After the demolition of Cherry Tree Farm in 1907, the land on which it had stood began to be developed. This plot was purchased from Miss Newbould by Bannister and Abbott, but because it was not designated as part of the original Meadow Bank Avenue Estate in 1896 it is not covered by Avenue documents relating to the period 1896-1909.

Bannister and Abbott made full use of the land’s potential. On the Avenue, they began building what would later become number 12 in September 1908. This was followed by numbers 10 and 8, which were completed in 1910 and 1911 respectively. All three of these detached Bannister and Abbott houses were constructed in the Arts and Crafts style; they are mentioned in Pevsner’s Buildings of England. There is an interesting family story behind the building of these homes which you can discover by reading Philip Marshall’s account in the Oral Histories section of the website.

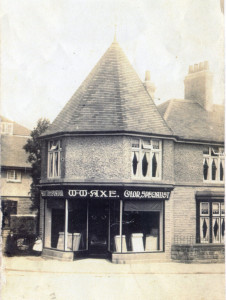

Behind these distinctive houses Bannister and Abbott had constructed more modest terraced properties, at the top of Machon Bank Road opposite the Union Inn. This development reflected the growing popularity of Nether Edge as an attractive suburb. On May 1st 1907 the firm applied to build four houses on Machon Bank Road but just a year later in May 1908 they reapplied to build nine. All were completed by August 1909.

The end house of this new, well-built terrace had a distinctive round ‘tower’ and this would become a shop, owned by local decorator, W. W. Axe. The photograph below shows his shop, with its fashionable arts and crafts lettering and display of wallpapers. Note also the children by the gate. This was probably taken c1915, by which time 8 Meadow Bank Avenue had been built to the left of the shop.Mr Axe’s shop at the top of Machon Bank Road c 1915

Mr Axe and his sons continued their business for many decades. They had premises on Cherry Tree Common (opposite the Union where the sheltered housing now stands), which were sketched by L.F. and T.M Flett in 1971. The sketches appear in Joan Flett’s book, Cherry Tree Hill and the Newbould Legacy, published by the Nether Edge Neighbourhood Group in 1999.

The first flurry of house building activity on her Meadow Bank Estate must have looked promising for Elizabeth Newbould but it’s clear that after 1900, with the exception of the Cherry Tree Farm land, there was a distinct lack of interest in buying the remaining plots.

The south side of the Estate was partially developed but, apart from the houses near the entrance to the Avenue, virtually the whole of the land on the north side remained unsold, along with three sections of the south side, mostly at the lower end of the Avenue. It wasn’t until 1909 that a second phase of developing the Estate commenced and this would have significant consequences for the Avenue’s future. Before we look at this second phase of development in more detail it might be helpful to have some understanding of these consequences. Nick Waite summed up the situation as follows:

“In August 1896 the whole development had been planned, the legal framework established and the first plots ‘Pre-sold’. The something happened, or rather did not happen, which Miss Newbould cannot have expected: in strictly commercial terms, the development was not a success. A modern developer might hope to complete an estate of 50 houses in a couple of years, or perhaps longer if he hit a recession: between 1890 and 1914 thousands of houses in scores of streets were completed and occupied in Sheffield. Yet it would be almost 40 years before Meadow Bank Avenue was complete, and by Miss Newbould’s death in 1909, after 13 years ‘on the market’, only about 17* of the houses had been completed. This slow pace of development had, or at least contributed to, three important consequences for the legal status and history of the Estate.” (*note: the 1909 sale plan shows 19 houses in place but perhaps not all were completed).

In Nick’s opinion, the three consequences of the slow pace of development were:

1. It could be the main reason why Meadow Bank Avenue remains private.

It may come as a surprise to learn that Elizabeth Newbould never stipulated that Meadow Bank Avenue would always be a private road, only that the Pleasure Ground should be for the private use of residents and their guests. Most roads created via the same model of development were adopted by the local authority within a few years of completion. The Avenue however remained (until the 1930’s) an uncompleted development, with an unmade road and a Pleasure Ground which would be expensive for the local authority to maintain. By then the residents had developed a way of managing things for themselves and wanted to protect the private status of the Estate, so it was never adopted.2. Leaseholding became common on the Estate.

This was because slow land sales prompted ‘special offers’ to encourage purchasers. In Sheffield this was frequently achieved by selling plots (either singly or in blocks) on very long leases, reserving for the original freehold owners a fixed annual ground rent. This enabled them to significantly reduce the price of the plots because they were guaranteed a reasonable return. The ground rents seem small now but c£8 per year would have been substantial in 1909 and the cost of buying a plot might be reduced by £200. At a time when a sizeable house could be completed for £700 this was an attractive saving.3. A new landowner entered the scene.

The third consequence of the slow development was what happened following Elizabeth Newbould’s death in April 1909, the disposal of her land and the emergence of an important new figure, Mr John Deakin. He was a Sheffield manufacturer, living at 85 Osborne Road and he bought 5 plots of land on Meadow Bank Avenue and Edge Bank at the auction sale for the disposal of Elizabeth Newbould’s land holdings. He quickly developed his plots and would also, in 1920, make a very significant change: he conveyed the road, footpaths and pleasure ground to Charles Wyril Nixon, a solicitor who had bought 10 Meadow Bank Avenue. Deakin was living in Scarborough by this time, so may have found it difficult to manage the Estate at a distance. Whatever his reason, Avenue residents have been responsible for managing the Estate ever since Deakin conveyed the responsibility to Nixon. From this point onwards, in Nick Waite’s words, “..the Estate was effectively a self-governing department, operating within the covenants and stipulations in the 1896 Deed and the individual leases of some of the houses… After the Deed of 1896, and the death of Miss Newbould and sale of her properties in 1909, this (1920) is the third and perhaps most significant date in the legal history of the Estate.”We’ll come back to the arrangements for managing the Estate in a later chapter but at this point let’s return to the events of 1909 and the second phase of building the Estate.

III. The Second Phase of Building the Avenue 1909-1920

Elizabeth Newbould died in April 1909. The auction sale to dispose of her estate took place just three months later, on July 6th 1909. It was a big sale and included ‘Sharrow Mount’ (the former family home described in Chapter 1), ‘Meadow Bank House’, land and properties on Osborne Road, Machon Bank Road, Cherry Tree Road, Kingfield Road, St Andrew’s Road, Lyndhurst Road, Chelsea Road and in Attercliffe. There were also 5 cottages and adjoining land on Edge Bank and 6 separate lots on Meadow Bank Avenue.

We have an original copy of the 1909 Sale Catalogue and this is the front cover.

The coloured plan below clearly identifies the plots for sale on the Avenue. It also shows us the houses that had already been built between 1896 and 1909. Within the Catalogue there is very detailed information about the covenants and stipulations contained in the Model Deed.

The coloured plan below clearly identifies the plots for sale on the Avenue. It also shows us the houses that had already been built between 1896 and 1909. Within the Catalogue there is very detailed information about the covenants and stipulations contained in the Model Deed.Sale plan 1909 showing lots on Meadow Bank Avenue and Edge Bank

The Meadow Bank Avenue Estate lots, which had remained unsold for so long, were all purchased on the day of the sale. John Deakin bought all the remaining land on the north side of the Estate by acquiring lots 3, 4 and 5. Significantly, under the terms of the sale, Lot 5 conveyed to the purchaser the roads, Pleasure Ground and footpaths. Under the terms of the Deed of Mutual Covenants this responsibility had been Elizabeth Newbould’s since 1896.

On the south side of the Avenue Deakin also purchased two vacant lots, numbers 6 and 8, and lot 7 containing 1,040 square yards of leasehold land which was already developed. Houses 40 and 42 had been built there.

There was another important lot for sale that day – Lot 9, the land and cottages of Edge Bank. This amounted to 2610 square yards and was bought by Thomas William Sorby, a Sheffield Iron Merchant. It was clear from the sale particulars that Edge Bank residents would have access to the Avenue road and footpaths, although there was no mention of the Pleasure Ground. The Custodian of the Avenue (Deakin) would have access to, and responsibility for, the pathway down Edge Bank. This was for the purpose of maintaining the Avenue sewers running under Edge Bank (these are marked on the Sale Catalogue map). The footpath down to Nether Edge also had to be maintained for Meadow Bank Avenue residents to access the shops and trams.Summary of Deakin’s 1909 purchases

- Lot 3: 3,290 square yards. This would become the site of numbers 5-15 but not all of the houses were built at the same time.

- Lot 4: 5,073 square yards was developed into houses 17-31.

- Lot 5: 5,275 square yards became numbers 33-43. This lot also conveyed to Deakin Miss Newbould’s responsibilities for managing the roads, footpaths, sewers and pleasure ground

- Lot 6: 1,026 square yards was developed into houses 14 and 16.

- Lot 8: 3,230 square yards. This would be developed into houses 44-54, but not until after 1920. Building was interrupted by World War One and the depression of the 1920

Deakin soon began to develop his newly-acquired plots. On the North side, E.Hart of Arundel Lane applied to build twenty houses on lots 3, 4 and 5 and White’s Directories show that numbers 5,25,27,29,31, 33,35, 37,39,41 and 43 were built and occupied between 1910 and 1917. The style of these homes was different from Avenue homes constructed in the first phase of building. Typical of the early Edwardian period, they had rendered or pebble-dashed external walls and plainer features inside. For example, the fireplaces and the woodwork on the staircases and skirting boards tended to be less elaborate than the Victorian villas. The designs incorporated attractive stained glass windows and door panels, many of which still remain.

Postcard showing the North Side of Meadow Bank Avenue c 1930, houses 17 – 39

Many of the north side houses also had large rear gardens, which stretched down to the boundaries of Meadow Bank House, Kenwood Park and land owned by Miss Rundle.

On the south side of the Avenue, Deakin’s Lot 8 became the site for a pair of semi-detached homes numbers 14 and 16. These houses were built by Bannister in 1915, completing the line of houses on the upper end of the Avenue. Although less obviously built in the Arts and Crafts style of the earlier Bannister and Abbott houses, numbers 14 and 16 sit comfortably alongside them. They are the only two semi-detached houses on the Avenue built to this particular design.IV. The Third Phase of Building the Avenue, 1920 – 1936

The remaining houses, 7, 9, 11, 15, 17,19, 21 and 23 on the north side; numbers 44 – 54 on the south side and 45, 47 and 47a at the end of the Avenue would all be built between 1920 and the mid 1930’s.

North Side:

Houses 17 and 19 were built in 1922. This was another example of a pair of semi-detached houses being bought by one family. The parents lived in one house and their daughter in the other. 21 and 23 were built around the same time; number 23 is pictured below.The detached house at number 7, and adjacent semis 9 and 11 were constructed during the early 1930s. Three very similar properties, numbers 45, 47 and 47a, were built at the lower end of the Pleasure Ground in 1935, on the remaining section of Wortley and Bush’s land; the very first Avenue plot sold in 1896. The houses were built by Mr George Jackson and were the subject of some debate according to the Minutes of the Avenue Committee Meeting held in March 1935. Members noted that permission to build three houses was being applied for, rather than two as originally envisaged. An investigation of the Covenant, revealed no grounds for opposing the proposal so one detached house and two semis were built. This explains why there is a 47a as well as a number 47.

The very last house to be constructed was number 15, which was completed on the remaining vacant piece of land (originally part of lot 3) in 1936. We have copies of the architect’s plans and the original bill for the completed house. It cost £878 0s 2d, but it appears from the receipt that the builder generously discounted the two pennies!Number 15: The last house to be built on Meadow Bank Avenue in 1936

There has never been a number 13 Meadow Bank Avenue. This is very common on residential roads because of the superstition surrounding the ‘unlucky’ number.

South Side:

Numbers 52 and 54 were the first of the remaining plots to be built upon on the south side; both were occupied by 1922. The picture below shows the houses with their wooden railings. These mirrored the railings on the walls of the Edwardian villas on the opposite side of the Avenue.52 and 54 Meadow Bank Avenue in the 1920s

Houses 44 and 46 were completed in 1929 in the vacant plot visible in the photograph above. These 3 bedroom, semi-detached houses had large bay windows and an oriel window in the small bedroom above the front door; a common feature in the late 1920s and early 1930s. To the rear of both houses was a small coal store because, unlike the Victorian villas next to them and most other houses on the Avenue, these houses had no cellars or basements. The remaining vacant land on the south side would be filled by another pair of semi-detached houses, numbers 48 and 50. They too were constructed in typical 1930s style.

Later developments; garages, extensions and conversions

Unlike many of the larger properties constructed in Nether Edge at the same time, none of the houses on the Avenue were built with space for coach houses. This reflected the economic status of the people who lived here. By the 1920s and 30s some residents began to own motor cars and this eventually led to the building of garages where space permitted, for example near the top of the Avenue. It wasn’t until the 1960s and 70s, however, that some of the Victorian villas on the south side had garages built into their basements.

In the period since the 1970s, many of the houses have been extended, by building conservatories or by converting roof areas and basements into additional living space. Despite these changes, the integrity of the Avenue has been preserved. We owe a great deal to the Deed of Mutual Covenants and the stipulations which have protected the usage, the building lines and the quality and style of the houses which make up our community. -

Chapter 3 – Managing the Avenue Estate

Chapter 3:

Managing the Avenue Estate.

Introduction

The purpose of this chapter is to explain how Meadow Bank Avenue has been managed and protected over the decades since it was built in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The fact that it remains a self-governing private estate makes it a special place to live and, for most of its history, the community of Avenue residents has been actively involved in the governance process.

Since 1896, the Meadow Bank Avenue Estate has been privately managed by its developers and residents. The systems for self-management have changed over the decades as have the titles of those who have undertaken the task. The different systems provide the structure for this chapter and can be simplified as follows;

• Sole Custodian, 1896-1934

• Custodian supported by an Advisory Committee, 1934-1962

• Joint Trustees , 1962-2013

• Company Directors, 2013 to present.The primary responsibility has always been to look after the fabric of the Estate – the road, pathways (including Edge Bank), trees and Pleasure Ground or Green, dealing with contractors and other outside partners to carry out these tasks. The work is funded via financial contributions levied from each household and it is the duty of those who manage the Estate to calculate and collect the agreed charge for each property on an annual basis. A bank account also has to be maintained and annual accounts prepared.

A second responsibility is to uphold the 1896 Deed of Mutual Covenants, ensuring compliance and dealing with any potential infringements. They have a duty to maintain the private nature of the Estate and fulfil the duties of ownership, for example public liability, insurance and relations with outside authorities. Avenue Minute Books (dating from 1934) provide a record of how this has been done. They also reveal some interesting examples of ‘social policing’ and various interventions in support of maintaining the Model Deed. Some of these will be looked at in a later chapter but first we need to explore in more depth the ways in which the Avenue has been managed and maintained since 1896.I. 1896 – 1934: Management by Custodian

The previous chapter explained how Elizabeth Newbould’s custodial responsibility for managing the roadway, pavements and Pleasure Ground of Meadow Bank Avenue (a duty she had fulfilled since 1896) was passed to John Deakin, when he purchased most of the Avenue’s remaining undeveloped plots of land in 1909. Deakin subsequently left Sheffield and in 1920 transferred the role of Custodian to solicitor Charles Nixon, the owner of No.10.

When Charles Nixon died in 1929 his widow assumed the responsibilities of Custodian. By 1934, however, Mrs Nixon and a solicitor’s clerk named Widdowson, acting as the executors of Mr Nixon’s estate, were asking to be relieved of the custodial duties. We don’t know how actively or effectively the Avenue had been looked after during the period 1909-1934 because, as far as we are aware, there are no surviving written records. From 1934, however, we have an archive of minute books, papers and annual accounts which detail the way in which the Avenue has been cared for and protected by its residents. These resources have been used to compile this chapter.

In accordance with the Model Deed of Mutual Covenants, the practice of levying a small annual charge for the maintenance of the Estate was in operation throughout this period. The Deed specified that the charge was calculated on a fixed Accounting Period ‘the year ending on the Thirty First of December next preceeding’ and payment by householders had to be made ‘on or within twenty one days after demand thereof’. It is probable that, at least until 1909, the collection and management of the charge was handled by Elizabeth Newbould’s Accountant, John Wortley. The money was used to pay for gardeners to maintain the Pleasure Ground and trees and for small repairs to the roadway and pavements.II. Management by Custodian and Advisory Committee 1934 – 1962

By the Autumn of 1934 almost all of the building plots had been developed and the houses occupied, but a potential crisis was looming and this would bring significant changes to the future management of the Meadow Bank Avenue Estate. On the 7th November 1934 a letter was drafted by Mr Percy J. Meneer, a solicitor and owner of No. 25, and Mr Ernest Swinscoe, owner of No. 30. It invited all residents to a meeting in ‘the ballroom’ of 12 Meadow Bank Avenue, the home of Mr Truelove. A replacement, or replacements, had to be found for the late Mr Nixon to take over the role of ‘Custodian’ and the need was particularly urgent because the road had deteriorated into a state of serious disrepair. One of the early postcards of the Avenue, dating from c1930, clearly shows the rough surface of the roadway at that time. There was no hard top surface to the road and the growing number of cars owned by residents and their visitors was causing it to erode.

As the letter below demonstrates, the deteriorating condition of the road was a problem which, if not addressed, could threaten the future status of the Estate:

Letter to Residents, November 1934

The sentence ‘There is grave danger of the Sheffield Corporation intervening by exercising their statutory powers’, is very interesting. It shows that there was genuine anxiety that the road might be adopted by the local authority – a move that would end the Avenue’s private status. The original Deed of Mutual Covenants of 1896, drafted by Elizabeth Newbould’s legal advisors, had envisaged and made provision for such a takeover of the Avenue’s infrastructure and maintenance by the local authority, should it become necessary. Although the statutory adoption of privately developed roads was a process that had become very common across the city’s suburbs, it was clear that this certainly wasn’t an outcome desired by the Estate’s residents. The meeting was to be a turning point because, from this time onwards, the Estate’s management and maintenance would be undertaken by a Committee of residents rather than a single Custodian.

The legal history and management processes of the Avenue become much clearer from this point. At the meeting Bernard Sanderson (owner of No. 35) agreed to have the Estate conveyed to him – but he would not be solely responsible for looking after its infrastructure. It was decided that he would be a Custodian supported by a small Advisory Committee of other residents and they would jointly make decisions.

The new Estate Committee held its inaugural meeting at Mr Sanderson’s house on November 27th. The first members were Messrs. P.J. Menneer, F. Marshall (Chairman), E. Swinscoe, C.E. Truelove, J.O. Vessey, C. Whittaker and B. Sanderson (Custodian). The official Minute Book was begun and records of the Estate’s management have been kept ever since. The first few years of the Minutes illustrate how the Committee operated and the tasks that it carried out.

Maintenance of the Estate was the Committee’s main responsibility and one of the early changes suggested by Mr Sanderson was the idea of ‘creating a fund for the ordinary management expenses of the Estate in order to remove the necessity of Mr Sanderson providing the money during each year’. It might come as a surprise to learn that one resident paid all the everyday running costs for the upkeep of the Avenue out of his own pocket – only recouping the money at the end of the year.

The costs incurred by Mr Sanderson were those associated with maintaining the Green, pruning the trees and generally keeping things neat and tidy. In addition there were expenses such as the Public Liability Insurance policy, which cost £1.0.0 per year, and other small expenses. These were all documented at year end and residents were recharged a portion of the costs according to the length of the frontage of their property (or properties). As can be seen from the Upkeep Account Summary below, the expenditure for 1934 was £26. 15. 5 and the contribution rate was 4d per foot – less than 2p per foot in modern currency.

Mr Sanderson’s suggestion was discussed by the Committee members and it was noted in the minutes (dated 18/12/1934) that, ‘whilst recognising the desirability of creating such a fund it was not deemed of such importance as to justify the cost and trouble of revising the Model Deed, but that owners who were willing to do so should be asked to deposit the sum of £1.0.0 for that purpose’: 35 out of the 42 home owners did agree to pay the £1 deposit the following year. The residents also agreed to pay their share of the bill for resurfacing the road. (see Chapter 4)

The charges for general expenditure were levied in accordance with the Indenture of 1896 which stated that; ‘ house purchasers had use of the roads, footpaths and Pleasure Ground on condition that they pay to the Custodian/Trustees, on or within 21 days after demand, such sums of money as should certify to be a fair proportion (according to frontage) of money expended during the year ending 31st December’.

Meadow Bank Avenue Upkeep Expenditure for the year ended 31st December 1934

By August 1935, only one resident had failed to pay the annual charge and her share of the bill for renewing the roadway. Despite several increasingly-irritated letters from Mr Sanderson the debt still stood, so the minutes from 28/8/1935 record that a solicitor was instructed, ‘to take such steps as he deemed advisable to enforce payment of the sum due (£10.4.3).’

From 1934 until July 1939 the Committee met very regularly, documenting their discussions and decisions in handwritten notes. The members’ role in maintaining the Avenue infrastructure during this period is covered in Chapter 4. From 1940 until April 1951 only the typed annual statements of accounts and expenditure are pasted into the Minute Book.

Upholding the Model Deed and Protecting the Avenue in 1939

The Minutes of the Avenue Estate Committee’s meeting on July 20th 1939 make reference to what would be a very significant intervention by the Meadow Bank Avenue Estate Committee. The action of the Committee effectively protected the Avenue for years to come. We have some original letters in the archive which explain in more detail what happened and how the Model Deed was upheld.

On the 17th July 1939, the City Engineer R. Nicholas drafted a letter to Custodian Bernard Sanderson. It was a notification that the Plans Sub-Committee was considering an application by the owner of No. 40, Mr George Harold Simpson, for permission to convert the house into two flats. Mr Nicholas wrote;

..‘in view of the fact that no other houses in Meadow Bank Avenue have been so converted I have been asked to communicate with you in order to ascertain the views of the Meadow Bank Avenue Estate Committee’.

A Committee meeting was quickly convened for the 20th July and the next day Mr Menneer (a solicitor and owner of No.25) sent a lengthy reply to Mr Nicholas, capturing the views of the members. The original letter is very faded but the text reads as follows;

Dear Sir,

‘We are to inform you that the Committee are unanimously of the opinion that the conversion of any house on the Meadow Bank Avenue estate would be detrimental to the general interests of the residents in the Avenue and the members of the Committee have satisfied themselves that their views are representative of the general body of residents. They instruct us to say that they will vigorously oppose any conversion into flats of any house on the estate and to express the hope that the Sheffield Corporation and the various committees interested will not accede to any such application.’

The letter set out five reasons for opposing the planned conversion,

- It began by quoting text from the 1896 Model Deed, setting out the constraints on usage imposed by the restrictive covenants, notably that properties should be private dwelling houses. It then went on to make the following points;

- That the fact that an owner of a house on the estate is not successful in letting the house on the terms he requires is no sufficient reason for dealing with it in a manner contrary to the restrictive covenants imposed.

- That such conversion into flats will inevitably seriously depreciate both the capital and annual values of all other properties in the Avenue.

- That the large preponderance of the properties in the Avenue are occupied by the owners.

- That the residents have always taken great interest in the preservation and maintenance of the common grounds of the Estate, engaging the services of a gardener as required for the purposes of the green and the topping and lopping of the trees and general upkeep of the roadway.

Planning Committees worked quickly in those days. On the 4th August 1939 Mr Nicholas responded, saying that the Special and Visiting Section of the Highway Committee had, on the 31st July, looked again at the application and had decided not to approve it. The decision was an important one for the Avenue. In the post-war period many of the larger houses in Nether Edge were converted into flats and bedsits, a trend which had a major impact on the appearance of both properties and streets. Fortunately Meadow Bank Avenue remained protected.

The advent of war in 1939 probably caused the initial break in the Committee’s meetings but there is no explanation of the post-war gap from 1945 until 1951. Reassuringly, when the remaining members of the original Committee, Messrs. Menneer, Swinscoe, Truelove and Sanderson, eventually reconvened on April 10th 1951, they began their proceedings by confirming that the minutes of the meeting held on July 20th 1939 were an accurate record – a remarkable feat of collective memory after a 12 year gap!

By 1951 the Estate Committee had lost its Chairman, Mr Fred Marshall, (he had died in 1941) and it also needed to replace members who had left the Avenue. Another meeting of residents was organised for 1st May 1951. The meeting took place at the Church Rooms, ‘Shirley’ on Psalter Lane and 28 households were represented. They approved three new Committee members, Mr Harold Kirkby (No.15), Mr John A. Smith (No.38) and Mr Laurence Smith (No. 44). As in 1934, the main business for discussion was once again the poor state of the road and a plan for improvement.

In 1953, after completing almost twenty years in the role of Custodian, Bernard Sanderson conveyed the Estate to John Arthur Smith, who undertook the responsibilities for the next seven years before leaving the Avenue in 1960. It was then conveyed to Frank Leslie Ashley, resident of No. 32. By this time there were also four Committee members; Douglas H. Williams (No.43), Mark Barber (No.27), Ronald B. Tobey (No.10) and Derek J. Walters (No.35). All had expressed their willingness to serve and had been approved in June 1958.

III. 1962 – 2013: From Sole Custodian to Joint Trustees

Leslie Ashley’s short term of office does not appear to have been a very happy one because in November 1962 he told the Advisory Committee that he would not be prepared to continue to act as sole Trustee (Custodian) of the Estate. From 1952 onwards, home owners had been paying a maintenance deposit of £4 per year, replacing the old system under which the Custodian had paid for all maintenance costs, only reclaiming them at the end of the year. It is clear from the minutes of 1961-2 that Leslie Ashley had struggled to collect deposits from some residents. This may have influenced his decision to end his role as Sole Custodian.He wrote to residents the following March stating;

‘Over the past two years I have become aware that, under present conditions, it is not possible for one man to make decisions acceptable to all the owners. May I suggest that FOUR JOINT TRUSTEES should be appointed, by popular vote. This is in order, as far as both the Trustee Act 1925 and our Deed of Mutual Covenants are concerned’ He added that, ‘If the owners wish, I am willing to receive nominations (ladies or gentlemen) from which the owners may elect the Trustees’.

This was a significant move because from this point onwards the Avenue Committee members would all have equal status and Mr Ashley’s suggestion of an elected body of Trustees was taken up; from then on Avenue residents would vote for their representatives.

The new group of successfully elected representatives comprised;

Hugh Greenshields – 24 votes

Ronald Tobey – 25 votes

Jim Swindells – 24 votes

Harold Kirkby – 20 votes

Eight households abstained from voting.

For the first time they were described as the ‘new Trustees’. We don’t know why the term of Trustee was introduced in 1963 because there was no change to the Trust Deed and no new responsibilities were assumed. In 1996 solicitor Nick Waite, who served as an Avenue Trustee in the 1970s, wrote about the change as follows;

‘It seems likely that the word Trustee was chosen, and has certainly been interpreted by successive Trustees ever since, to express the view that they should act only in the interests of residents and to preserve whatever the residents perceive as the valuable aspects of the community.’

The Treasurer of the Estate, Ronald Tobey, died in 1972, and the wishes of the three surviving Trustees (Messrs. Greenshields, Swindells and Kirkby) also to resign from their duties led to a further small refinement in the governance of the Estate, namely a move to a system of electing Trustees on a fixed term basis. In a letter of October 1972 circulated to all households, Hugh Greenshields explained that,

‘the present Trustees have approached a number of residents and have ascertained that several would be willing to serve – if duly elected.’

We don’t know how these willing residents were identified as suitable candidates but, as the letter below shows, there were eight candidates for the four positions of Trustee. All of them were men. Each household was entitled to one ballot paper.

Initially the returns were slow, so residents were issued with a postcard reminder at the end of October 1972 and a deadline for voting was set for 7th December. By then 36 ballot papers had been returned and 14 households had abstained.

The result of the election was not clear cut. Three Trustees, Barry Craven, Nick Waite and Philip Marshall, were duly elected but three others, Messrs. Kemp, Pearson and Williams, tied for the fourth vacancy. Votes were checked by an external independent source (a Sheffield Accountant) but the result remained unchanged, so a pragmatic decision was taken in January 1973 to have 6 Trustees instead of 4 and to share the workload to make it more manageable. The tasks were devolved as follows;

Nick Waite Chairman/Secretary Philip Marshall Treasurer Barry Craven Maintenance of Green/Roadway Mr Pearson and Mr Kemp The Annual Bonfire Mr Williams The Christmas Tree and Carol Singing The division of roles shows that the Trustees had absorbed additional social functions by this stage, although these were nothing to do with their legal functions. There were many more children living on the Avenue by the 1970s and the bonfire, carol singing and summer party (from 1977) all became part of the informal social life of the Avenue. They have continued ever since but are now organised by other volunteers and informal social committees. (For more information on this see Chapter 5.)

Elections have taken place ever since 1962. The first woman to be elected was Jennie Henderson (No. 35) in 1984, 18 years after Mr Ashley had proposed inviting both ‘ladies and gentlemen’ to stand for election. Once elected, Trustees could opt to serve for a single four-year term or a maximum of two terms. A staggered system of replacing two Trustees every two years was adopted from 2000 to ensure continuity. The full list of Avenue residents who have served as Trustees is included below.

1962-1972 Ronald Tobey, Hugh Greenshields, Harold Kirkby, Jim Swindells

1972-1976 Barry Craven, Philip Marshall, Nick Waite, R J P Kemp, H W Pearson, B Williams

1976-1980 Barry Craven, Philip Marshall, Nick Waite, Bob Young

1980-1984 Philip Allison, Martin Cowell, Alan Foster, Bob Young.

1984-1988 Jennie Henderson, Alan Foster, Chris Walker, George Kirkpatrick

1988-1992 Elizabeth Cousley, George Kirkpatrick, Alan Phillips, Peter Vaughan

1992-1996 Elizabeth Cousley, Sue Curtis, Alex Pettifer, Peter Vaughan

1996-2000 John Austin, Vincent Green, Gill Redfearn, Barbara Ward

2000-2002 John Austin, Vincent Green, Alison Bloxham, David Levine

2002-2004 Alison Bloxham, David Levine, Piers Proctor, Hilary Taylor-Firth

2004-2006 Piers Proctor, Hilary Taylor-Firth, Michael Bayley, Sue Wormald

2006-2008 Michael Bayley, Sue Wormald, Gordon Macnair, Roger Mayblin

2008-2010 Gordon Macnair, Roger Mayblin, Dave Kirkup, Lyn Bonnett

2010-2012 Lyn Bonnett, Dave Kirkup, Garth Lawrence, Sandra Pettifer

2012-2014 Robert Wormald, Sandra Pettifer, Gordon Macnair,

2014-2016 Robert Wormald, Amanda Drake, John Bartlett, Ian France

The degree to which the selected/elected representatives have consulted with other Avenue residents has varied considerably over the last eighty years. Broadly speaking, consultation and communication has increased with the passing of time. Until 1934 most decisions were taken by a single individual, the Custodian. After that, the Advisory Committee generally took decisions without any wider discussion. It was only when major expenditure was required that the residents received any communication other than the annual statement of Avenue accounts.

The Trustees now consult on all major changes, issue regular newsletters (a practice introduced in 1996), and all residents are invited to an Annual General Meeting, the first of which was held in 1998. At the AGM the Chairman’s report for the previous year is presented, there is a review of the financial position and feedback from the Social Committee on the year’s events. Future developments are discussed and the AGM also provides a forum in which residents are able to raise any issues of concern such as crime, anti-social behaviour and parking.

IV. 2013: The development of the Company – Trustees become Directors

This section of Chapter 3 explains the most recent changes in the Avenue’s governance arrangements, which took during the period 2010-2013, culminating in the formal incorporation of Meadow Bank Avenue Estate Limited at Companies House on 14th June 2013.

At the January 2010 Annual General Meeting, residents agreed to an investigation of a more formal management system for the Meadow Bank Avenue Estate. There had been a number of concerns on the part of the Trustees and it was recognised that the work undertaken by Trustees, and their responsibility for managing the finances associated with that work, had become increasingly complex with the passage of time. Three main issues were causing concern;

- The lack of accountability of the Trustees

- The informal nature of procedures, which relied largely on goodwill, common sense and good luck

- The personal financial exposure of the elected Trustees who, since 1963, had assumed collective ownership of the communal parts of the Estate.

The investigation was undertaken by Gordon Macnair (No. 40) and in September 2010, after extensive research, a Discussion Paper was circulated to all residents of the Avenue and Edge Bank. This identified the issues and options for future governance arrangements.

Options considered ranged from establishing the Estate as a Charity, a Formal Trust, a Limited Liability Partnership, Company Limited by Share Issue, Community Interest Company, Industrial and Provident Society and Company Limited by Guarantee. Each was carefully appraised, resulting in the opinion that a Company Limited by Guarantee appeared to be the most appropriate model for the future governance of the Avenue.

The details of such a proposal would need to be worked up but the Trustees’ intent was to make the change a technical one, while preserving and strengthening the cooperative nature of management of the Avenue. Transition to Company status would also increase the openness and accountability of the Trustees to the Avenue’s residents.

A simple table format was used to illustrate what would change and what would remain the same under the proposed new arrangements;

Changes Stays the same Work through written rules, drawing on good practice, eg from charity websites Rules written to reflect largely what we do now Processes and procedures written down in a simple framework Actual processes of management and maintenance continue as now Trustee-Directors’ accountability to residents becomes formalised through the membership process Directors (formerly the Trustees) work for the general good of the Avenue Election of Trustees-Directors by members is required Directors (formerly the Trustees) will be drawn from the Avenue. Four year cycle continues MBA Covenant transfers to the Company as the new owner of the central space – Green, roads and pathways Unchanged text of the Covenant between owners (now the Company) of the central space and householders Non-profit written into the Articles Non profit making Remove unlimited personal liability of the Trustees Still need public liability insurance The Discussion Paper examined whether, under the proposed new Company arrangements, there would be adequate safeguards against bad things happening, for example a deterioration of the common space, undesirable building development or Directors’ failure to submit annual returns leading to penalties under Company Law. It was felt that the move to the new Company would strengthen the formal links between Directors and Company Members (Residents) and improve accountability by writing specific requirements into the company governing documents.

The suggested benefits of the proposed new Company were summarised as follows;

- It would help to structure the ways in which Trustees work, increasing openness and transparency to residents

- Trustees as Directors would be formally accountable to the residents as Members, thereby increasing accountability to residents.

- It would make contracting with outside bodies easier because this would be done by the Company rather than an individual Trustee.

- There would be no need to re-register ownership of the Avenue to new Trustees every four years. Company Director registration can be done online.

- It would completely remove a risk to Trustees that they would be held personally liable for accidents arising to third parties on Avenue property.

The response to the consultation paper was very positive; 36 households replied, all supporting the broad approach of a move to a Company Limited by Guarantee. Of these, 6 households offered further help with the transition and were recruited into a ‘sounding board’ process.

In January 2012 the AGM continued the discussion on the standing of Edge Bank relative to the Avenue, with Trustees reporting that research showed there was evidence to suggest that ownership of Edge Bank rested with the Trustees. In view of this, Articles were drafted so as to allow discretion on including Edge Bank households as members of the company. This would also give them the same rights and responsibilities as Avenue members.

On the 14th June 2013 Meadow Bank Avenue Estate Limited was formally incorporated at Companies House. Membership was agreed to cover all Avenue households with one vote per household. In the same month each household was invited to join. By the time the first Company AGM took place in January 4014 all of the Company’s formal processes had been set up, including its Articles and supporting Rules and 47 households had become members. The same AGM decided to invite households from Edge Bank to join the Company, however by the 2015 AGM no household from Edge Bank had chosen to do so. Membership by Avenue households had risen to 49.

A separate issue that had been touched on at the January 2012 AGM was the question of moving to a uniform annual charge for each household. This would replace the system of individual charges calculated on the basis of house frontage measurements, which had been in place since Herbert Heap’s survey in 1934, when money needed to be raised to fund the renewal of the roadway. The AGM decided that this change would be better done once the new Company was up and running.

There followed another extensive consultation on this issue and in January 2015 the results were presented to the AGM. There was overwhelming support for the proposal to levy Avenue charges on a single flat rate basis per household.

The Avenue’s first Company Directors have managed a very important change in the Estate’s history. One of their early decisions was to establish an Avenue website. This hosts the Company’s records, minutes of meetings and legal documents. The website also houses material from the Estate archive, enabling us to publicly record (for the first time in its history) the story of the Estate’s governance.

-

Chapter 4 – Maintaining the Estate

Chapter 4:

Maintaining the Estate

In this next chapter we look back through the Avenue archives to see how the Custodians, Trustees and Directors have maintained the infrastructure of the Estate . What have been the main issues? Who has looked after our beautiful Green and trees and what have been the significant changes to the fabric of the Estate since 1896? These are some of the questions that we’ll be trying to answer in the course of the chapter. In Chapter 3 we saw how the Avenue had remained private for 120 years through the efforts of its custodians and residents. An important part of that process was the annual physical ‘closure’ of the Estate.

I. Protecting the Private Status of the Avenue; the Annual Closure of the Gates